Estimates are a Business Function, not an Engineering Function

“We just landed one of the biggest deals in our company’s history. To close the deal, we promised the customer a few things. I trust you to make it happen.”

The conversation ended with the famous last words: “Don’t worry, what they want is really basic.”

During the deal our CEO, CTO and CPO got together and decided that what the customer was asking for was simple and easy to build. They made commitments to the customer without involving any engineering teams in the process. To top it off they agreed to a date and threw it over the fence as well.

When questions came up about what the customer wanted our CTO said “figure it out”, or “do whatever you think would be best”.

Has that ever happened to you? If it makes you angry consider this - The C-Suite wasn't estimating the time to build the feature, they were estimating what they needed to win the business. Successfully, I might add - job done by the C-suite!

Now that the business has been won, your job is to manage the customer while the project is completed in whatever time it takes. The customer might not know exactly what they wanted, or maybe they were just pushing to see how much your company wanted the business. Maybe they actually wanted the requirements to be vague that they could change things as the project went along while keeping you (the vendor) under pressure to deliver whatever thing(s) they eventually decide they want.

What matters is your company won the deal, and managing the customer is now your most important job, not necessarily delivering specific features.

Twelve rules of estimates

1. Estimates are a business function, not an engineering function.

Estimates are used to make promises to external customers. Estimates are used to promise features (Hey Elon, when is "full self-driving" actually going to be available?). Estimates are used to plan future events (e.g., we need to have "X" feature ready for the summer sales conference). Finally, estmates are used to make business decisions on feature value.

Once you realize this, you can approach estimating differently. You may ask "What do we need to know to make this decision?" If this feature takes over a year to develop, is it worth doing? Or, we can ask the development team "what are the odds this feature can be developed in less than a year?" From there we can make an informed business decision.

Or, if we need something to show at the next sales conference then the question is not "will this specific feature be ready?" but rather "What can we have ready for the upcoming meeting in two months?"

2. Reality is unaffected by estimates.

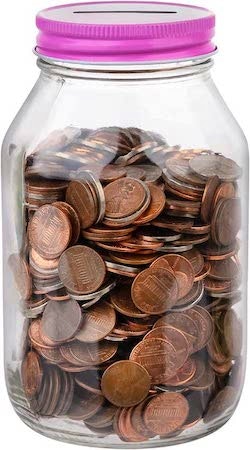

How many pennies are in this jar?

Whatever estimate you come up with, whatever methodology you used, I bet your estimate is wrong. It's either more or less wrong, but it's not exactly right.

Now for the key point: your estimate does not influence how many pennies are present. Reality is unaffected by your guess.

The same logic applies to estimating or forecasting software delivery timelines. Delivering a feature still takes a certain amount of time, regardless of the estimate. Software delivery cannot be late or early - it simply takes whatever it takes. It is our expectations that create a perception of late or early delivery.

To be fair, pushing for a lower estimate can be valid when discussing a story with a colleague in your team and when it's backed up with facts. However, if the stakeholder making this claim is not part of the development team, doesn't know what needs to happen when implementing the story, and doesn't bring any new facts then:

"Pushing for a lower engineering estimate is like negotiating for better weather with a meteorologist."

3. Estimates are just predictions.

It’s also generally a prediction we make with too little information. When doing complex work, at the start we know we lack information. Our information and understanding are limited to the extent that getting the estimate close probably means we we have some experience, but we also got lucky, just like when guessing the number of pennies in the jar.

One of the best tools for estimation, is not an estimation technique at all, but a communication technique. Try giving 30/60/90 estimates:

- I'm 30% confident it'll be done in 20 days,

- 60% confident it'll be done in 45 days, and

- 90% confident it'll be done in 60 days.

If the product manager or sponsor say "great, we'll plan on 45 days," remind them that there's 40% odds we don't hit that. If management responds "Could you make that 90% and 25 days?", or if they simply complain that the range is too wide ("How can it be 20-60 days? I need more confidence!") then you can use that as justification for exercises which increase confidence (prototyping, more detailed planning, research any unknowns, etc).

The important thing is to make it impossible for someone receiving your estimate to ignore the uncertainty in the numbers.

4. The only thing worse than estimating is imposing estimates on others.

Nothing is more frustrating than forcing estimates on a team. Because those estimates will turn out to be incorrect, the team that tries to deliver on them will develop feelings of resentment toward those that produced the original estimates.

Throwing estimates over the fence is a sure-fire way to start a blame game where everybody blames each other. At a minimum - involve those responsible for delivery in the estimation process.

5. Estimates become more reliable closer to the completion of the project (when they are the least useful).

Early on in a project, you know the least, so your estimates will be the least accurate. Paradoxically, this is also the moment when you’d like to know most about the required effort of your project, as you can pull the plug on the project without having to exert any effort.

As the project progresses, you will gain a better understanding, and have a lot more information about what needs to happen. Your estimates will become significantly more accurate. However, as more and more of the project is completed, the accuracy of your estimates becomes less important. Also, because of the time you’ve already invested in the project, companies become less likely to change the business decision (i.e. quit development).

6. The more you have to worry about your estimates, the more certain you can be that you have bigger things you should be worrying about instead.

Estimates are a red herring. It’s easy to get distracted and believe accurate estimates and meeting timelines are what matters most. However, as said before, it takes what it takes.

When teams try to meet the imaginary timeline produced by the crystal ball, tunnel vision creeps in. The only thing everyone sees is the looming deadline. The whole discussion reverts to ‘How can we meet that deadline?’ while ‘Is it good enough?’ moves to the backseat, and ‘How can we move faster?’ climbs into the driver’s seat.

Obsessive focus on ‘When will it be done?’ guarantees you will move quality to the backseat. Yet, "am I doing high quality and high value work?" is the most important question in the long run.

7. When you suck at building software, your estimates will suck. When you’re great at building software, your estimates will probably still suck.

The ability to estimate accurately has little bearing on your ability to build great software.

Better teams will usually produce better estimates, but those better estimates still aren’t good enough to deliver accurately.

Like the weatherman who cannot predict the weather accurately more than a week in advance, software development teams quickly reach a ceiling in how accurately, and how far in the future, they can predict outcomes.

"Instead of being angry at the winds you will never be able to predict and control simply adjust your sails."

8. The biggest value in estimating isn’t the estimate but rather creating a common understanding.

When estimating, a different estimate usually means there is a conflicting understanding of what needs to happen. By talking about the work to be done, differences in opinion of what needs to happen surface.

Creating a common understanding is the biggest value in estimation, not the actual estimate itself (which will turn out to be wrong).

9. Keeping things simple is the best way to increase the accuracy of estimates.

Removing complexity and uncertainty, either by doing the work or before you start doing the work, is the best way to increase accuracy of estimates. Keeping things simple is the best way to prevent your estimates from ballooning.

10. Building something increases the accuracy of estimates more than talking about building it.

It’s appealing to talk, analyze, design, debate, and do infinite research before starting the work to abolish all uncertainty and risk. However, no matter what you do, you’re still limited to the knowledge of what you can know before starting the work. You quickly experience diminishing returns from trying to draw conclusions based on inadequate information.

By doing the work and starting, you discover the real problems that matter sooner. Work with what you do know to discover what you don’t know. Being book smart won’t cut it, you need to be street smart too.

My grandfather always said: "The sooner you start, the sooner you finish."

11. Breaking all the work down to the smallest details to arrive at a better estimate means you will deliver the project later.

Our usual response to produce a better estimate is to sit endlessly in meeting rooms and break everything down to the smallest detail. By doing this, we lose valuable time we could spend actually doing the work. As stated before, this is where you discover the problems that matter.

On top of this, all those elaborate plans are detached from reality and will ultimately slow you down more and more as the project goes on (because you will have to continually explain why your plan is not matching reality).

Sticking to the plan as it deviates more and more is a dangerous thing. It is better to start with simpler plans that are easier to adjust. When you break down the whole project to the smallest details, you create a false sense of precision.

However, you can add more detailed breakdowns as you progress and learn.

12. Punishing wrong estimates is often like punishing a child for something they don’t (and can’t) know yet.

Some companies believe that it’s possible to produce perfect estimates as teams mature and become stronger. Therefore, any team that is not able to produce accurate estimates is incompetent.

When you punish teams for making inaccurate estimates, you are likely penalizing them for things that are out of their control.

It’s like punishing a kid for something they can’t and don’t understand yet. It’s a form of bullying that leads to panic and anxiety without producing any tangible benefits.

Stop wasting time on the delusion you will ever be able to produce perfectly accurate estimates and focus on making sure your team is always working on the highest value items.

Summary

If you’re confident you’re making the best progress you can towards delivering something valuable, does it make a difference if it’s slower (or faster) than expected? Especially if that expectation was flawed and imprecise to begin with?

Communication is always key - as the effort more becomes clear, keeping management updated about new information, new challenges and particularly progress towards the goal is critically important. As long as the organization (or client) feels part of the process and has current information the friction will be lower. Most importantly, staying focused on quality and a value will never steer you wrong in the long run.

"Hofstadter's Law: It always takes longer than you expect, even when you take into account Hofstadter's Law."