The Inertia of Enterprise Despair

As of this writing, in early 2019 Sears announced it is near liquidation, with a $4.4B bid to keep operating. At the same moment, on the same day, Amazon.com is the most valuable company in the world with an $810 billion dollar valuation, or 184 times greater.

Prior to Amazon's founding Sears had everything going for it. Brand recognition and established customer base, check. Global supply chain, check. Top notch distribution operation, check. System and infrastructure to take orders and handling billing, check. Bricks and mortar stores in addition to catalog sales, check.

Unfortunately for an incumbent, change is much harder than anyone ever imagines it to be.

"...Most organisms are highly resistant to change, but when they die it becomes possible for new and improved organisms to take their place. This rule applies to social structures such as corporations as well as biological organisms: very few companies are capable of making significant changes in their culture or business model, so it is good for companies eventually to go out of business, thereby opening space for better companies in the future."

— John Ousterhout, Stanford University (My Favorite Sayings)

There is a huge gulf between the speed and agility of a digital start-up and a large, entrenched incumbent. Not only do enterprises lack the proper digital skills, they simply cannot respond fast enough to react. This inertia has a name - it's called the Inertia of Enterprise Despair. It is made of these components:

- Institutional Inertia

- Cost Allocation

- Risk Management

- Talent

- Security

- Outdated Paradigms

- Regulation

- Procurement

- Legacy Systems

- Change Control

1. Institutional Inertia

Large incumbent enterprises exist because they did things right. They made good choices, hired good people and created outstanding products and services. The fact they were so successful under the old paradigms is exactly what makes it so hard to adapt to new ones.

Transformation by consensus, or by occasional hackathon, will not work, because transformation is not iteration from a low baseline: it requires making fundamental changes to an organization’s structure and processes. Digital transformation is about business transformation. It involves making fundamental changes to the organization's core processes and workforce.

Enterprises are realizing they are now becoming software companies, and the people running a software company need to know how to do that. Organizations that want to thrive in the digital age need to wield the political will to radically transform themselves, rather than adopting superficial solutions. They must redesign how they operate, redesign their internal structure, and re-staff. Given what we know about the challenges of organizational change this will likely fail.

What works better is to create a "digital" organization that is segregated the parent company. This new organization can recruit the talent it needs and operate like a startup. The challenge is to make this new organization as separate as possible; it has to be able to choose what corporate functions it taps into, otherwise it is yoked to the same "chassis" as the parent.

Many organizations have created in-house VC funds to seek out promising startups and take a stake in them to secure their digital future. This approach creates the maximum amount of independence and separation. This is the clearest way to compete on a level playing field with the "Industry+Tech" startups that plan to make you irrelevant.

2. Cost Allocation

Poor cost allocation models create all manner of suboptimal enterprise behavior. They create a sense of helplessness for the department receiving the allocation. Leaders on the receiving end feel they are unable to manage the allocation amount or service level. Maybe they would like a lower (or higher) service level and are willing to sacrifice (or pay) for the privilege. But there are typically limited options, generally "one price, one service level".

Worse, the models that build up the costs to be allocated are only known inside the allocating organization and rarely reflect reality. If the organization receiving the allocation wants to "pull out" and buy the service from a third party they are usually told they can't because that would simply drive up costs for the remaining business units (same pie, bigger slices).

Leaders conclude that if they can't change the allocation they can make damn sure to get the best possible service level. So they begin to beat on the organization supplying the service. This of course eventually ruins the working relationship between them and continues until all parties thoroughly dislike each other. It goes without saying that things do not move quickly or efficiently at this point because the parties stop speaking to each other, and in really bad cases they actively sabotage each other.

Cost allocations must be completely transparent, and both costs and service levels must be benchmarked against the market. The receiving organization must be given the freedom to opt out. Finally, the enterprise must recognize that many costs should simply not be allocated, especially for those centralized services that divisions or subsidiaries are forced to adopt.

3. Risk Management

Risk management is by definition meant to reduce risk, which also by definition promotes the status quo.

Enterprises have well-developed risk management muscles, particularly in regulated industries like healthcare or financial services. Since technology is the basis for nearly all business processes within a financial services company, the Risk Management function is always very interested in the consequences of a significant IT failure/outage, or a data breach.

They are so interested that they become very involved in key functions like project delivery and change management. The effect of this involvement is lots of documentation and meetings, two things that are sure to slow anything to a crawl.

Like some aspects of security, occasionally the risk management activities are referred to as "risk management theatre". It exists to show we have it, and it's primary purpose is management reporting. It is less clear if it truly averts risk - particularly "black swan" type risks. It is usually focused on issues that either occur regularly, or at least have already occurred in the past. It rarely anticipates issues that have never happened before, but of course those are the most important risks to avoid.

The financial crises of 2009 is a great illustration. Does anyone think Bear Stearns or Lehman didn't have a risk management function? Of course they did - they just didn't anticipate or understand the actual risks facing them.

It’s interesting how risk managers and internal auditors react to Black Swans. Typically swooping in after the outage, keen to bayonet the wounded, with a mandate to add more controls. Making damn sure to close the barn door after the horse has bolted.

Risk Management should a) be skilled enough to actually have a conversation about IT architecture because that is what determines how resilient a company's technology really is, and b) figure out how to reduce their "friction" to a technology adoption - which they have zero incentive to do.

4. Talent

An organization is only as good as it's people. Successful organizations start out with great people. Great people help build the company and many successful careers are built as the company matures. Over time the great people go on to other challenges, or they retire. New leaders must take the reins, usually people who grew up inside the company and respect the culture and track record that made the company successful. These people are terrific choices for continuity, and maintaining the status quo. Conversely if the market really changes, and the company has to reinvent itself, these leaders struggle.

As the company grows it will develop a strong HR organization with all the best intentions. The HR professionals will perform their duties with professionalism and dedication. Unfortunately through hiring practices and compensation practices they will force the workforce to become "average" rather than exceptional.

Hiring Practices

In a startup the founders are usually A+ players who saw an opportunity and were potentially frustrated with the ability to go after it inside their former employers. These people recruit and hire the "A players" they know from within enterprises struggling under the yoke of the Inertia of Enterprise Despair. They don't spend a lot of time formalizing job descriptions or titles, they don't benchmark their salaries - they just grab the best people they can and go for it.

Conversely, in a large organization the process goes something like this:

Step 1: Conduct a job analysis

Basically, this step will allow the human resources manager, hiring manager, and other members of management to determine if we really need this new position and define what the new employee will be required to do in the new position.

Step 2: Create a job description

Before anything else, the organization must first define exactly what it needs. Job analysis involves identification of the activities of the job, and the attributes that are needed for it. These are the main parts that will make up the job description. According to human resource managers, the job description is the “core of a successful recruitment process”.

-

Define minimum qualifications. These are the basic requirements that applicants are required to have in order to be considered for the position. These are required for the employee to be able to accomplish the essential functions of the job.

-

Define a salary range. The job must belong to a salary range that is deemed commensurate to the duties and responsibilities that come with the position. Aside from complying with legislation (such as laws on minimum wages and other compensation required by law), the organization should also base this on prevailing industry rates. For example, if the position is that of a computer programmer, then the salary range should be within the same range that other companies within the same industry offer. (see how the concept of "average" sneaks right in?)

Step 3: Sourcing of talent

Usually there is a rule that says the job must be offered internally first. This simply slows things down and wastes time - there is no reason why internal candidates cannot be evaluated in parallel with external candidates. In fact it makes more sense because you are looking at all possibilities rather than just candidates from a shallow pool - after all you want the best candidate right? Yet large companies have this speed bump. Once you review the internal candidates and politely tell them "no, but thank you for applying" (usually creating some form of ill will) you can move forward.

In a startup you hire the best people you know from places where you have worked or consulted. Talent is easy to spot when you work side by side (but difficult to uncover in a 60 minute interview). Assuming you can convince them to join, you pay whatever is necessary to get them because you know they are "A players".

Conversely, in a large company the hiring manager rarely does any sourcing at all - it is HR's job to go source candidates. Yet most people in HR don't truly understand the roles they are recruiting for, relying on the job description and salary band to source a few decent resumes.

Step 4: Making of the job offer

The last step of the previous phase involves the selection of the best candidate out of the pool of applicants. It is now time for the organization to offer the job to the selected applicant.

Assuming the person accepts, the new employee will still have to undergo pre-employment screening, which often includes background and reference checks. When all these pre-employment information have been verified, the employee will now be introduced to the team.

Meanwhile, in the startup the "A player" has been on the ground for two months and already built the first MVP product.

Compensation Practices

As a company matures and it's industry grows benchmarking becomes increasingly important to the management team. This is especially pervasive inside HR organizations in enterprises in mature industries.

All benchmarking is an imperfect science but compensation figures are collected annually by large HR consulting firms and then sold in the next budget/compensation cycle. This means the data is already stale and a year old when you get it.

Enterprises all say they want the best people, yet they attempt to benchmark their compensation to the average of year-old stale data. True A players get offered jobs elsewhere and leave, and the enterprise is left with average players at average compensation - exactly what the process is designed to produce.

5. Security

If you’re working on something significant in a large enterprise, such as a new product, or implementing new software, then it inevitably becomes necessary to get a ‘security sign-off’.

Processes around this vary, but essentially, one or more security experts descend at some point on your project and audit it. It’s a medieval trial by ordeal. You get poked and prodded in various ways while questions are asked to determine weaknesses in your story. There will likely be references to various 'security standards' which in turn are enforced with differing degrees of severity.

The beatings will continue until the security weaknesses are identified (I’ve never heard of there being none). The outcome is a report outlining the set of risks that have been identified. These risks may need to be ‘signed off’ by someone senior so that responsibility lies with them if there is a breach. That process in itself is arduous (especially when the senior management person doesn’t fully understand technology) and will be repeated on a regular basis until the risks are sufficiently ‘mitigated’ through further engineering effort or process controls.

The real issue is very few senior leaders understand technology security and into the knowledge gap flows money and resources. The result is "lots of security" with questionable real effectiveness, measurable increases in cost and schedule, and measurable decreases in productivity (and possibly the morale of capable engineers) across the company.

6. Outdated Paradigms

"What’s your oldest Excel spreadsheet still in use?" This question was asked recently in an online discussion group. A lively conversation ensued where people tried to outdo each other.

"I just realized that a spreadsheet I use weekly was first created in 2004 and has been in constant use now for over 13 years!"

The winners (or losers depending on your perspective) were several organizations still using spreadsheets from 1995, the year that Excel began to take root with the launch of Microsoft Office for Windows 95. Hopefully they are now using a modern version of Excel. Yet these files — and the 'business logic' they contain — are still working for them, some twenty-three years later.

Can enterprises using spreadsheets from 1995 transform into digital winners? Will their employees be able to redesign the process from the ground up using modern technology. Unlikely.

“You take the new thing and shove it into the old paradigm”.

— Rob Wolcott, Professor of Innovation & Entrepreneurship, Northwestern Kellogg

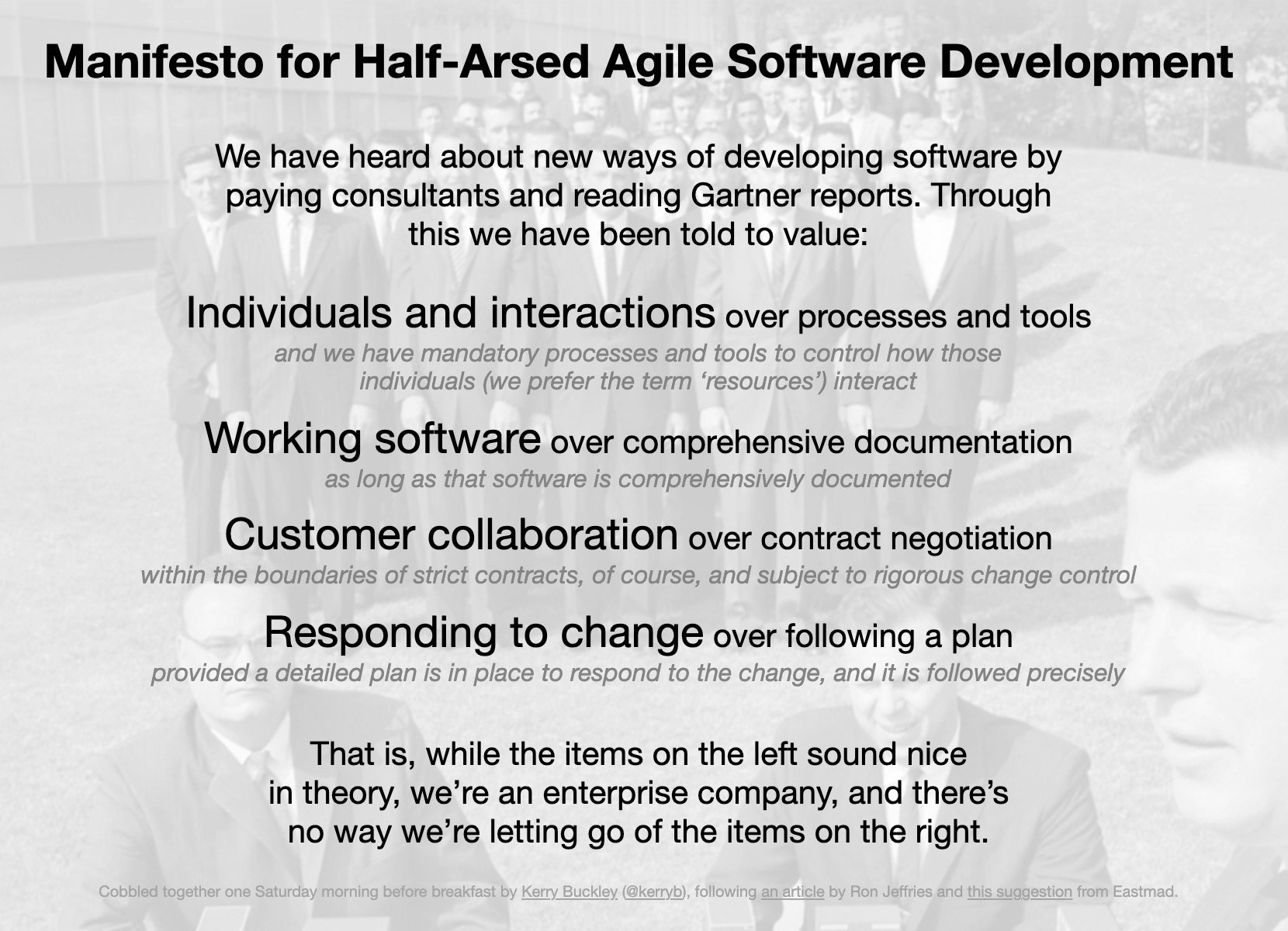

Agile-ish and Scrum-Theater

Many companies embarking on ‘digital transformation’ are "consciously incompetent". They know what’s not working, and they know they have skill gaps and process issues, but are under the illusion that if they just adopt "the right process" it will save them. These companies frequently adopt an Agile or Lean process in name but not in practice. This is what’s sometimes referred to as agile-theater.

If your software team is the only Agile part of the product team, that’s agile-theater. If the product manager is from the technology team, that's agile theater. At this stage you’re probably gathering little or no market feedback. Product backlogs are prioritized around dev and engineering and not for customer value. Product teams are rushing to build solutions first before validating market value or product/market fit.

You Must Start with a Product Vision

Why do you need a product vision? Because it simultaneously aligns your product with a customer pain point or need, while filtering out who on your team will stay and who will go.

Here’s how that works. A product vision inspires some and scares others. While a company mission sets the purpose for why a company should exist, a product vision suggests a future state in all it’s glory. It’s a great filter to motivate and activate the best in your supporters. It’s also a great way to get fence-sitters to decide where their loyalty lies and possibly ‘get them off the bus’.

If your highest paid people are driving opinion then consider the impact on your transformation. If they lack the fluency and literacy required to guide the business through change then you’re not going to get far. The product vision and strategy must be owned by the person who is responsible for the product itself, not someone who sits at a higher level in the org chart. That person must be competent and understand "product/market fit" and get paying customers as fast as possible, and then iterate even faster.

There is no finish line. Digital isn’t something to be achieved. It’s state of being.

7. Regulation

Regulators have power derived from government. They are able to enforce fines, penalties, and changes to business structure or processes. They have the force of law and global enterprises fall under the regulatory regimes of many different governments. It quickly becomes a nearly impossible task to track global regulatory compliance.

So to ‘simplify’ things large enterprises often create a set of rules that cover all the regulations that may ever apply to their business across all jurisdictions. Those rules are generally the strictest you can imagine. Added to that, those rules are curated by the legal/compliance organization and develop a life and culture of their own within the organization independent of the regulator - such that they can’t easily be brought into question.

These rules become huge inhibitors of change. Regulators embrace paradigms that are rooted in the experiences of software built in previous decades - because that is what worked back then. And if you want to change that, it will itself likely take years and agreement from multiple parties who are unlikely to want to risk losing their job. So you can end up in a situation where you are forced to work in a way prescribed years ago by your internal legal and compliance team, which are in turn based on interpretations of regulations which were written years before that, all based on software development processes that were in vogue years before that!

Obviously, this slows things down further and makes change quite difficult. Want to bring development and operations closer together and form a "DevOps" team? Well that's not how we did it 25 years ago! Therefore it's not recognized as best practice by the regulators and would definitely be frowned upon.

8. Procurement

As an enterprise grows up it suddenly wakes up one day and realizes there are 50 departments/divisions/subsidiaries all buying "widgets" and if it could just coordinate and consolidate all "widget spend" it would save money. The logical thing to do is to create a centralized purchasing function to acquire widgets at the lowest possible price.

There are so many ways in which this perfectly sensible idea goes wrong. The first of which is that the new head of widget procurement and the widget procurement officers and analysts all must justify their roles. It wouldn't make sense spending $1M annually to operate our widget procurement office while only saving $500k on widgets, would it?

The logical responses are:

-

Attempt to create more savings. Let's squeeze the widget vendors harder, cut down the number of widget vendors so we have more leverage, commit to certain levels of widget spend, etc. If all goes well we will save even more money! However, the widget procurement process is now slower and less responsive to business needs. We may be saving on widgets but it may take months longer to buy widgets due to extensive negotiations. We now may be committed to buy a certain number of widgets - and if our needs change those savings may evaporate. We usually alienate our suppliers through this process so they have very little incentives to go "above and beyond" when called for. Finally, vendor consolidation may leave us more vulnerable to vendor risk. The fact our risk went up, our vendors don't like us anymore, and our agility went down, are very real costs, but unfortunately they are hard to quantify and therefore don't count.

-

Put the savings in a better light. I have seen savings estimated off the "highest widget price" vs. the "average widget price". Or, based on what widget prices are expected to be in the future. Or, based on some external benchmark like "industry average widget price". Anything that can be used to make our savings figures look as good as possible. Is this cynical? Yes. Does it really happen? Yes.

-

Cast a wider net. Are we not saving enough on widgets to justify a department of widget procurement? Easy - what other things do we buy that the procurement office can help with? This is where technology always comes into focus. Technology is a large spend in any enterprise and that makes it an attractive target. However, buying technology is not the same as buying widgets.

First of all, technologists who are making big platform technology acquisition decisions have to look years into the future. Whatever decisions taken today will affect an enterprise for a long time. We have to meet with the vendors and understand their roadmaps. We must evaluate their underlying architecture. We must understand the ecosystem they operate in. This knowledge comes by building relationships with Value Added Resellers (VARs) and the vendors themselves.

Once we make a purchasing decision we expect the VAR, or occasionally the vendor, to help us with bringing the new technology online. We expect security advice, configuration support and advice, and deployment help. These services may not be explicitly called out, or priced in a bid, but they are very important and valuable. Success or failure may hinge on these services.

What happens when procurement gets involved? First, they usually make sure that technical people have no direct control over the negotiation (or sourcing process). Second the relationships that technology has nurtured over time migrate to procurement, disconnecting the technology practitioners, and making it difficult for them to get the information they need to be effective going forward.

What often happens is something close to this:

- You go to senior person to get sign-off for a budget for purpose X

- They agree

- You document several options for products that fulfill that purpose

- The sourcing team will take that document and negotiate with the suppliers

- Some magic happens

- You get told which supplier "won"

This process helps reduce the risk that someone has undue influence to push a particular vendor (there are strict rules around accepting so much as a coffee from a potential supplier), which is a good thing. On the other hand, this process does extend the timeframe and can add months.

To complicate matters further, sourcing might have its own preferred supplier lists of companies that have been vetted and audited in the past. If your preferred supplier isn't on that list (and hasn't made a deal with one on those list), the process will take even longer or stall.

To add insult to injury those "valued added" services your VARs used to provide are no longer provided because they were either squeezed out in the negotiations, or you have lost the relationship capital you formerly had.

The enterprise "saves money" by trading against the costs of delay, lack of agility, and treating supplies as adversaries instead of partners. You didn’t get your twitter account by putting out an RFP for a "microblogging service" right? Enterprise software companies now actively work to circumvent procurement offices by keeping initial costs low or non-existent and delivering their software via a web browser. Once the software is established, it is likely some "enterprise features" will be required that are then expensive to acquire.

Old school vendors who operate under a licensing model become predatory (examples: Computer Associates, Oracle, Adobe) with frequent licensing audits. If a company's procurement office is not sufficiently aligned with the IT organization these audits can be train wrecks.

Centralized procurement is not required for contract language standardization. In most organizations, even those without centralized procurement, the contracts are still reviewed by legal. Legal can enforce standard contract language regardless of centralized procurement.

Some risks can be managed by staffing the centralized procurement office with experienced technology procurement officers who act as "consultants" to the IT practitioners (so the vendor relationships are not disrupted). VAR services should be called out and valued. Time must be valued in some fashion - how do we expose the cost of delay against the potential for additional savings and make good decisions?

9. Legacy Systems

All large enterprises have a base of legacy applications and code; plus legacy people, with legacy skills to care for them. New, younger employees view working on this stuff as career suicide and run as far away as possible. Unfortunately legacy applications are always at the heart of the enterprise's most basic business processes - after all they were so important they were the first automation projects in historical times.

More automation grew around them and integrated with those systems, taking into account their data structures and quirks. Then even more automation was layered on top of that, and later we added data warehouses, web architecture, and bolted on analytics. Replacing legacy systems is like open heart surgery on an elderly patient - wonderful news when it works, but funeral arrangements must be made if it doesn't.

"If it ain't broke, don't fix it!"

It becomes nearly impossible to gain sponsorship to replace legacy systems because of the inherent costs and risks. What executive wants to sponsor a legacy system replacement when they can instead champion a new predictive analytics system or a brand new web site? So these systems lumber on like large ancient beasts, cared for and fed by a tribe that speaks "assembly", "VSAM", "JCL" and "COBOL" and communes with companies that were dominant when "I Dream of Jeanie" was on TV. Of course there is no current documentation of how the system works or what the system does - it exists only in the heads of the tribe members.

CIO's talk about reducing "run" costs to free up resources for "change". Legacy systems usually have many years of intricate patching and modifications making them very brittle and difficult to change. Older hardware and software may require added compatibility layers to facilitate integration with "modern" hardware and software. All of this drives up the run costs. The key issue is how do you materially change your run costs without ever having the sponsorship, resources and political will to tackle the legacy systems? I suppose it's for the same reason that some of us smoke and are overweight; we know it's bad for us but somehow the will to change evades us.

The net effect is, like an athlete, the enterprise can run only as fast as it heart can beat and it's lungs can breathe. Legacy systems are not "real-time", but rather "batch", so the heart only beats once a day (or maybe several times per day). The large enterprise with legacy systems and software at its heart cannot keep up with younger, fitter rivals.

10. Change Control

In an enterprise, especially in a regulated industry, there is always some kind of system that tracks and audits changes to ensure that changes don’t happen without due oversight. This is because auditors love this kind of stuff. To ensure "audit-ability" of changes there is a process:

-

Changes must be raised to the "change control board", which normally requires filling out an onerous form.

-

Then the form must be approved/signed off by anyone responsible for any area that may be impacted. So let's say we are making a network change. Since every service runs on top of the network, every person responsible for every service will have to sign off. In theory, the person signing off must carefully examine the change to ensure it is sensible and valid. In reality, most of the time trust relationships build up between change raiser and change validator which can speed things up.

-

There might also exist ‘standard changes’ or ‘templated changes’, which codify more routine and lower-risk updates and are pre-authorised. These must also be signed off before being deployed (usually at a higher level of responsibility, making it harder to achieve).

-

Then the compliance, risk and security officers have to weigh in and approve the change.

-

The the approved change will be reviewed and ratified by the change control board and only then can the change be implemented.

-

Changes are scheduled into predetermined change windows, but only so many changes can fit into any one window, and common wisdom is to not make too many changes at once, so some changes will be pushed to the next available window.

-

While in theory the change can be signed off in minutes, in reality change requests can take weeks or months as obscure fields in forms are filled out wrongly (‘you put the wrong code in field 44B!’), sign-off deadlines expire, change freezes come and go, and so on.

-

As a result there is sometimes the concept of an "emergency" change request that very senior people can approve and basically "push it through". However, very senior people don't like approving emergency changes and ask lots of uncomfortable questions.

All this makes the effort of making changes far more onerous than it is elsewhere, which enforces the status quo.