The Man Least Likely to Succeed in Politics

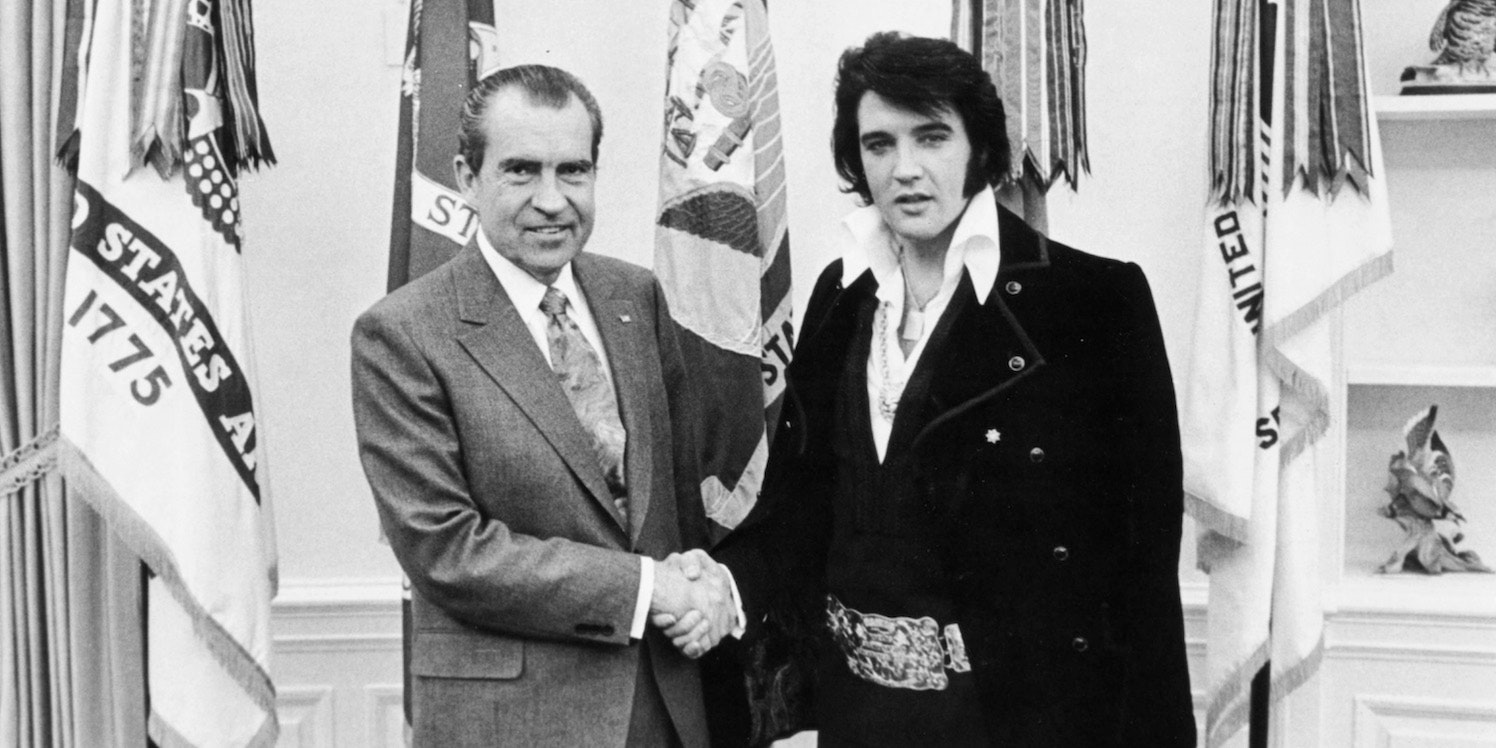

Dick Nixon understood that getting the smart, popular kids to vote for you didn't matter. He called the popular kids "Franklins" and he called his kind the "Orthogonians". Nixon discovered that being hated by the "Franklins" was no impediment to political success.

Franklins were well-rounded, graceful, moved smoothly, talked slickly. Nixon’s new club, the Orthogonians, was for the strivers, those not to the manner born, the commuter students like him. He persuaded his fellows that reveling in one’s unpolish was a nobility of its own...

The Orthogonians’ base was among Whittier’s athletes. On the surface, jocks seem natural Franklins, the Big Men on Campus. But Nixon always had a gift for looking under social surfaces to see and exploit the subterranean truths that roiled underneath. It was an eminently Nixonian insight: that on every sports team there are only a couple of stars, and that if you want to win the loyalty of the team for yourself, the surest, if least glamorous, strategy is to concentrate on the nonspectacular—silent—majority. The ones who labor quietly, sometimes resentfully, in the quarterback’s shadow: the linemen, the guards, the punter. Nixon himself was exemplarily nonspectacular: the 150-pounder was the team’s tackle dummy, kept on squad by a loving, tough, and fatherly coach who appreciated Nixon’s unceasing grit...

Nixon beat a Franklin for student body president. Looking back later, acquaintances marveled at the feat of this awkward, skinny kid the yearbook called “a rather quiet chap about campus,” dour and brooding, who couldn’t even win a girlfriend, who attracted enemies, who seemed, a schoolmate recalled, “the man least likely to succeed in politics.” They hadn’t learned what Nixon was learning. Being hated by the right people was no impediment to political success. The unpolished, after all, were everywhere...

— Rick Perlstein: "Nixonland: The Rise of a President and the Fracturing of America"

The unpolished, after all, are everywhere.

Trump reached out to those who are:

- Less suspicious of patently false claims

- Less willing to do their research and homework

- Less tolerant of people of different races

- Less tolerant of people of different religions

- Less tolerant of female leadership

- Less tolerant of "tree huggers"

How do you reach these people?

Mostly they no longer read the LA Times, the New York Times, or the Washington Post (many probably never did). They no longer watch the evening news with Dan Rather. Rather, they glance up from Snapchat to see who got the rose on The Bachelor.

Social media is how you reach these people. One consistent theme across both the Trump victory and the Brexit success was their use of "advanced marketing techniques". These campaigns utilized the power of emotion to drive their narratives and leveraged the complexities of Big Data to direct those messages at segmented groups via social media with devastating effect.

One connection between the Trump campaign and the Brexit campaign was the alleged involvement of communications firm Cambridge Analytica (CA) of which allegedly Steve Bannon was formerly chairman of the board.

Cambridge Analytica used psychometric profiling to identify potential voters and to inform their approach and rhetoric in reaching them. Psychometrics allows the utilization big data to assess vast numbers of people and construct personality profiles on each person in order to pinpoint individuals most likely to convert.

Cambridge Analytica claims to have up to 5,000 data points per person – and they’re talking about almost every person in the United States, plus many more worldwide.

How do you build a profile of a person?

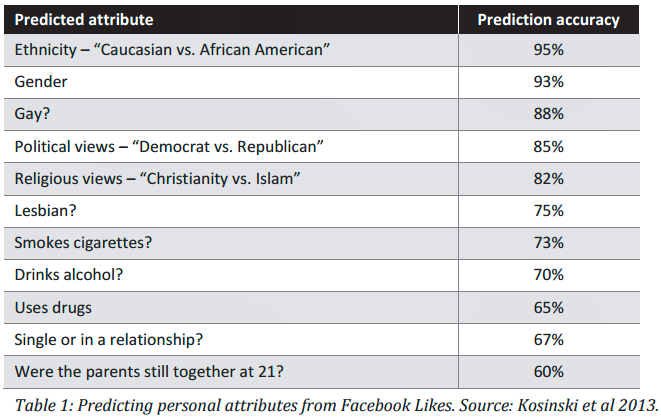

Interestingly, by studying a person's Facebook "likes" researchers can know them better than their spouse. Michael Kosinski, when researching at Cambridge University, created an experiment where he posted a free-to-access psychometric test online to gather small amounts of data to inform his data analysis. This test went viral on Facebook and Kosinski was able to draw some powerful conclusions from his study.

“Kosinski continued to work on the models incessantly: before long, he was able to evaluate a person better than the average work colleague, merely on the basis of ten Facebook “likes.” Seventy “likes” were enough to outdo what a person’s friends knew, 150 what their parents knew, and 300 “likes” what their partner knew. More “likes” could even surpass what a person thought they knew about themselves.”

With 170 likes per person, Kosinski’s methods were able to predict the following attributes with the connected rates of accuracy.

Can this information be used to influence voters?

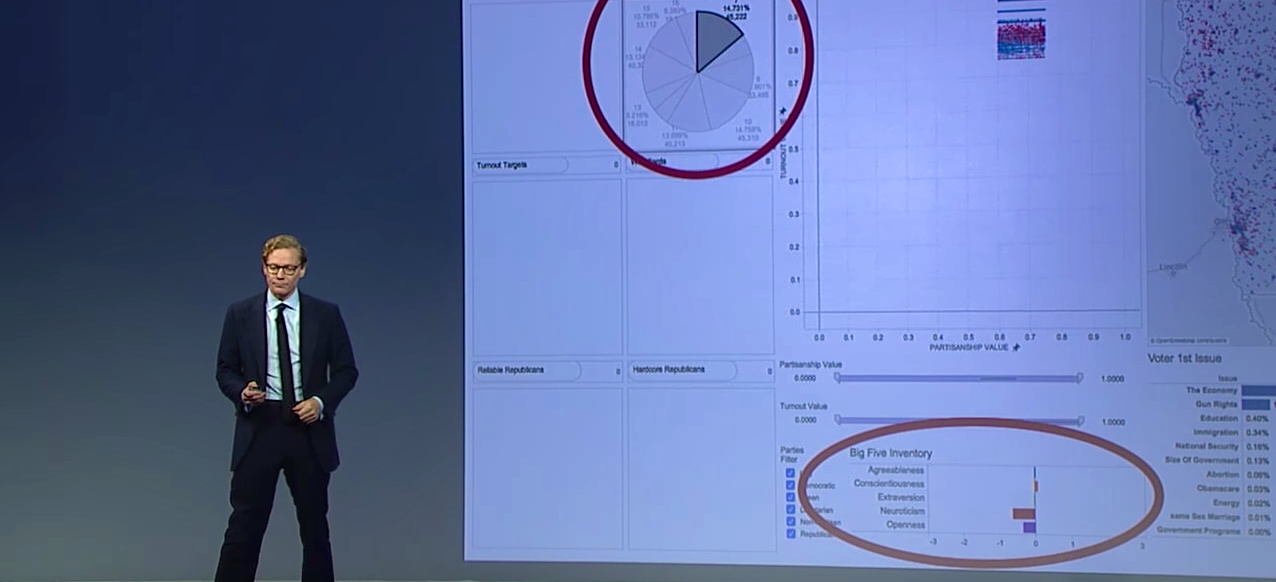

One psychometric framework is known as The Big Five, or OCEAN. This approach is centered around summarizing an individual’s personality through relation to five key categories:

We know this methodology is employed by Cambridge Analytica as their CEO Alexander Nix is pictured here below giving a presentation with the Big Five methodology taking center stage as one of the ways of understanding data.

A politician in a US election needs to appeal to more than 65 million people in order to win the election. You need to find people susceptible to your product or message and be able to convert them. This is where the psychometric emotional mapping techniques offered through the Big Five methodology can help.

The Need for Cognition Scale

Another method to target voters is called the Need for Cognition Scale. This method is used in psychometrics to measure “the extent to which individuals are inclined towards effortful cognitive activities”, or feel “a need to understand and make reasonable the experiential world”.

This scale is used to understand how big an impact emotions make upon an individual’s decision-making process. Persons low on the Need for Cognition Scale tend to form their opinions based heavily on emotion.

Our research finds that Trump has attracted a disproportionate (and unprecedented) number of “low-information voters” to his campaign. Furthermore, these voters are more likely to respond to emotional appeals — whether about the economy, immigration, Muslims, racial relations, sexism, and even hostility to the first African American U.S. president, Barack Obama. They are the ideal constituency for a candidate like Trump.

We define low-information voters as those who do not know certain basic facts about government and lack what psychologists call a “need for cognition.” Those with a high need for cognition have a positive attitude toward tasks that require reasoning and effortful thinking and are, therefore, more likely to invest the time and resources to do so when evaluating complex issues. Those with a low need for cognition, on the other hand, find little reward in the collection and evaluation of new information when it comes to problem solving and the consideration of competing issue positions. They are more likely to rely on cognitive shortcuts, such as “experts” or other opinion leaders, for cues.

— Richard Fording and Sanford Schram: "‘Low information voters’ are a crucial part of Trump’s support", Washington Post, November 7, 2016

Voters who score poorly on the Need for Cognition Scale are easier targets to sell political ideas to. They are the easiest group of floating voters to target and capture based on a emotional message, delivered or shared by somebody they trust.

Can Social Media be "weaponized" to exploit targeted voters?

We know there are millions of fake accounts and highly active bots on all the social media platforms. Since these companies are valued by the number of accounts they have, or the number of accounts acquired, or "active users", they have little incentive to block the creation of fake accounts and activity bots.

Italian security researchers Andrea Stroppa and Carlo De Micheli, in a report released four years ago, in 2013, claimed that they found 20 million fake accounts for sale on Twitter. Jason Ding, a research scientist at Barracuda Labs, told NBC News that the number of Twitter accounts that were fake was "at least 10 percent, maybe more." Twitter, according to The Wall Street Journal, claimed in its Securities and Exchange Commission report that only 5 percent of its accounts were fake.

The people who run the fake accounts and the bot farms where you can buy followers on Twitter, or likes on Facebook, are no longer selling fake persona, they are now selling political influence. Why buy just buy fake followers on twitter when you can tweet some fake news and have thousands of retweets?

Bots can also be used to silence people with opposing views. An automated army of pro-Donald J. Trump chatbots overwhelmed similar programs supporting Hillary Clinton five to one in the days leading up to the presidential election, according to a report published Thursday by researchers at Oxford University.

The bots targeted people by a hashtag symbol, like #Clinton. Their purpose: to rant, confuse people on facts, or simply muddy discussions, said Philip N. Howard, a sociologist at the Oxford Internet Institute and one of the authors of the report. In some cases, the bots would post embarrassing photos, make references to the Federal Bureau of Investigation inquiry into Mrs. Clinton’s private email server, or produce false statements, for instance, that Mrs. Clinton was about to go to jail or was already in jail.

UPDATE 04/29/2017: Facebook has published how clusters of fake accounts were used to disseminate and amplify "fake news" during the 2016 election cycle.

UPDATE 10/12/2017: What Facebook Did to American Democracy The Atlantic has published what is currently one of the best, in depth looks at how social media and Facebook specifically was used to influence our presidential election.

Quotes from the article:

The same was true even of people inside Facebook. “If you’d come to me in 2012, when the last presidential election was raging and we were cooking up ever more complicated ways to monetize Facebook data, and told me that Russian agents in the Kremlin’s employ would be buying Facebook ads to subvert American democracy, I’d have asked where your tin-foil hat was,” wrote Antonio García Martínez, who managed ad targeting for Facebook back then. “And yet, now we live in that otherworldly political reality.”

Through 2015, Breitbart went from a medium-sized site with a small Facebook page of 100,000 likes into a powerful force shaping the election with almost 1.5 million likes. In the key metric for Facebook’s News Feed, its posts got 886,000 interactions from Facebook users in January. By July, Breitbart had surpassed The New York Times’ main account in interactions. By December, it was doing 10 million interactions per month, about 50 percent of Fox News, which had 11.5 million likes on its main page.

A Guardian reporter who looked into Russian military doctrine around information war found a handbook that described how it might work. “The deployment of information weapons ‘acts like an invisible radiation’ upon its targets: ‘The population doesn’t even feel it is being acted upon. So the state doesn’t switch on its self-defense mechanisms,’” wrote Peter Pomerantsev.

Jonathan Albright, research director of the Tow Center for Digital Journalism at Columbia University, pulled data on the six publicly known Russia-linked Facebook pages. He found that their posts had been shared 340 million times. And those were six of 470 pages that Facebook has linked to Russian operatives. You’re probably talking billions of shares, with who knows how many views, and with what kind of specific targeting.

Add everything up. The chaos of a billion-person platform that competitively dominated media distribution. The known electoral efficacy of Facebook. The wild fake news and misinformation rampaging across the internet generally and Facebook specifically. The Russian info operations. All of these things were known. And yet no one could quite put it all together: The dominant social network had altered the information and persuasion environment of the election beyond recognition while taking a very big chunk of the estimated $1.4 billion worth of digital advertising purchased during the election.

UPDATE 03/16/2018: Facebook suspends Trump-affiliated data firm over privacy concerns Politico informs us that Cambridge Analytica has been suspended after Mueller requested emails from Cambridge Analytica’s Trump-affiliated employees in connection with the probe into Russian election meddling.

UPDATE 03/19/2018: Facebook Executive Planning to Leave Company Amid Disinformation Backlash Alex Stamos, Facebook’s chief information security officer, plans to leave Facebook by August. He had advocated more disclosure around Russian interference of the platform and some restructuring to better address the issues, but was met with resistance by colleagues, said the current and former employees. In December, Mr. Stamos’ day-to-day responsibilities were reassigned to others.

Closing the Deal

Once a voter has been "sold", or converted, then “confirmation bias" takes over. Confirmation bias is the tendency people have to embrace information that supports their beliefs and reject information that contradicts them. Of the many forms of faulty thinking that have been identified, confirmation bias is among the best catalogued; it’s the subject of entire textbooks’ worth of experiments. If reason is designed to generate sound judgments, then it’s hard to conceive of a more serious design flaw than confirmation bias.

However, people are not randomly wrong. Presented with someone else’s argument, we’re usually quite adept at spotting the weaknesses. Almost invariably, the positions we’re blind about are our own.

References

- Massive networks of fake accounts found on Twitter 1 in 10 Twitter accounts is fake, say researchers

- What Marketers Can Learn from Trump About The Science of Persuasion

- Who shares the story, not who reports the news, is what counts for casual readers

- Project on Algorithms, Computational Propaganda, and Digital Politics

- Automated Pro-Trump Bots Overwhelmed Pro-Clinton Messages, Researchers Say

- How Pro-Trump Twitter Bots Spread Fake News

- Facebook under fire for fake news, but the platform will never take real responsibility.

- Why Facts Don't Change our Minds

- Need for Cognition Scale

- Sources of Trump Support: The Case of Low-Information Voters

- ‘Low information voters’ are a crucial part of Trump’s support

- Information Operations and Facebook

- What Facebook Did to American Democracy